“It astonishes me sometimes — no, often — how every person I get to know — everyone, regardless of everything, by which I mean everything — lives with some profound personal sorrow. Brother addicted. Mother murdered. Dad died in surgery. Rejected by their family. Cancer came back. Evicted. Fetus not okay. Everyone, regardless, always, of everything. Not to mention the existential sorrow we all might be afflicted with, which is that we, and what we love, will soon be annihilated. Which sounds more dramatic than it might. Let me just say dead. Is this, sorrow, of which our impending being no more might be the foundation, the great wilderness? Is sorrow the true wild? And if it is — and if we join them — your wild to mine — what’s that? For joining, too, is a kind of annihilation. What if we joined our sorrows, I’m saying. I’m saying: What if that is joy?”

Ross Gay, The Book of Delights (h/t Marginalia)

Month: April 2022

No, we don’t need a flier

Expedit esse deos, et, ut expedit, esse putemus.

Ovid, Ars Amatoria

If you want to see an academic outreach librarian sigh using only their eyeballs, ask them if they can make you a flier.

It’s a running joke among colleagues in my field of work that if you discuss promotional efforts long enough, someone will always recommend making a flier. An 8.5×11 inch flier… that they can attach to an email.* There is something strangely definitive about making a flier: as if it adds legitimacy (and perhaps finality?) to the promotional process. Or perhaps this only applies to those who worked in a world before the emergence of social media.

In “The Human Element”, Loran Nordgren talks about “fuel vs. friction” in promoting new ideas. When we are pitching a new idea, product, or service to an audience, our impulse is to add as much “fuel” to the pitch as possible. For example:

- here are all the reasons why you should come to our library event,

- here are some flashy graphics about the new service we’re offering students, or

- here are some really trendy tchotchkes for taking our survey, or

- here is a flier.

All of these well-meaning incentives are intended to fuel people’s desire for what we’re offering, but as Nordgren points out, it’s unlikely to move the needle in your direction. In some cases, it will have the opposite effect.

Instead, Nordgren’s research shows the reducing barriers, or “friction”, is the best use of our time and resources. Maybe it’s not that library events are not appealing, but remembering the date and time is an extra hassle. Maybe it’s not that no one finds library consultations useful, but coming to the library is just that much extra effort. Maybe it’s not that no one wants to complete our survey, but having to go through DUO authentication one more time is just… too much.

For library events, what if we sent text message reminders to anyone who signed up to be alerted about new events? For library consultations, what if we offered them on Zoom? For our surveys, what if we set aside time to have students complete those surveys during library instruction sessions?

None of these solutions are novel, but it is easy to forget how everyday, seemingly mundane barriers keep us from making connections with library users. I am lucky in that I work on a campus where affinity for the library is remarkably high. We don’t need more fuel to communicate the value of the library (e.g., more emails, more signage, flashier swag); we need to reduce barriers to engagement. As I am thinking about ways to expand library outreach next year and working with my team to improve our work, I am keeping Nordgren’s work in mind. Where can we reduce friction?

*I’ve always wondered what people think the recipient will do with that flier. Do you think faculty will print it out? Students certainly will not: do students even have personal printers anymore? Have you ever tried reading an 8.5×11 flier on a mobile device? Do you enjoy constantly swiping left and right to get the whole thing in a 16:9 frame? I am sighing so hard with my eyeballs right now.

(image source: Men at a public library in Malmö 1949)

This is not going to go the way you think

I don’t think academic libraries need social media.

I say this as someone who has run social media accounts for academic libraries for almost a decade. Granted, the social media landscape has changed quite a bit in the last 10 years, but I think this has always been true and I’ve only just begun to realize it.

Currently, I’m working on a literature review about how academic libraries justify their use of social media and what assessment methods they use to bolster that justification. I’m focusing on articles published in the last 5 years and I’m starting to see a general trend in the narratives. It goes something like this:

- Libraries need to be on social media because of X (where X is typically something you would expect, like engagement, communication, or marketing to students).

- Ok, so let’s assess how well social media does X.

- Hm, the data doesn’t make a strong case that social media does X.

- Well …

It’s at this point that I start tensing up. What are the authors going to do next? In too many cases, they go on to say something to the effect of: “Oh well… We should still be on social media anyway!”

What? You just found evidence that something is not working and you’re just going to keep doing it anyway? There’s an apocryphal Einstein quote about that. (The quote is actually from a 1981 Narcotics Anonymous pamphlet, via Rita Mae Brown’s 1983 book Sudden Death.)

We have come to a point where everyone (well, not everyone) assumes that maintaining an institutional social media account is something we must do, despite evidence that it is not producing the results that we would like it to produce. In their 2017 article, “Social Media Use in Academic Libraries: A Phenomenological Study,” published in the Journal of Academic Librarianship, Harrison et al. describe this phenomenon as it relates to the content of academic libraries’ social media:

“The high level of correspondence in codes and themes were interpreted by researchers to mean that academic libraries are using social media in a homogenized manner, suggesting the presence of institutional isomorphic mechanisms (mimetic, and normative forces). Given that isomorphic forces impose conformity, but do not necessarily coincide with efficiency or effectiveness, awareness of these isomorphic forces is valuable to academic libraries. This new knowledge offers libraries the opportunity to evaluate the degree to which they have traded conformity for efficiency and effectiveness. If the tradeoff is determined to be less than ideal: academic libraries may consider requirements for establishing a social media strategy that best suits their organization as opposed to using a onesize fits all approach.”

This concept of “institutional isomorphic mechanism” comes from earlier sociological research cited by Harrison et al. Basically, institutions within any given profession start to copy and adopt each others’ actions and structures over time. This mimicry helps maintain legitimacy and “in-group” status, but sometimes at the expense of function and outcomes. As the authors note: “Regardless of efficiency or evidence of potential efficiency, organizations will adopt formal structures that align with institutional myths in order to gain legitimacy, resources, stability, and enhanced survival.”

I don’t think academic libraries’ inability to quit social media is driven by an insistence on engagement. As some of the articles I’m in the process of reviewing show, engagement on social media is tepid at best. And I would suspect that many us in outreach work would readily admit that social media engagement is an poor substitute for interacting with students in other ways.

We maintain diamond hands on social media accounts due to the (mostly unsupported) expectation that it is an effective communication tool. We want people to know about the library. On social media, we can pump out endless amounts of information: new collections, old collections, new programs, throwback programs, technical updates, deadlines, etc. It’s our personal megaphone! We easily fall into the trap of posting about a new program or initiative on social media and saying to ourselves “Done! Now people know about it.”

Except that no one is listening.

If our goal is to increase engagement online, we need a shit-ton more resources. Full-time, dedicated teams that can strategically build the brand: developing high-quality video content, working with campus influencers, and experimenting with emerging platforms. It would require more targeted, fine-grained assessment (and probably the use of personal data that would make most librarians squirm), more financial investment in ways to expand our reach (read: paid advertising), and way more yarrr! content!

Alternatively, if our goal is simply communication, there are more effective methods.

For example, if you set up a table outside the library and talk with students as they walk by, I guarantee you will speak with more students in a couple hours than might read a tweet in an entire day. Moreover, your interactions with them will be stickier and more impactful. Instead of spending an hour crafting the finest carousel of Instagram images for the library’s page, you could spend that same time crafting content for the university’s main channels and reach a larger audience. You could draft blurbs for other units’ newsletters, go on a roadshow to different departments on campus, develop vanity publications for key stakeholders, or work with student influencers. All would have a deeper impact than relying entirely on social media for outreach needs.

If you can do both, great! But most of us are working solo and thus choices are necessary. Unless you have a team (or at minimum a full-time employee) dedicated to social media, you are going to get more bang for your buck (read: impact) spending your energies elsewhere.

Does this mean I think academic libraries should simply shut down their Instagram accounts tomorrow? No, that would be reckless and unnecessarily disruptive. But I do think exploring the idea of “what would it look like if we did?” might serve as useful exercise in strategic thinking. Plotting the path between here and there by exploring how we might substitute the creative energies we spend on social media to communicate in other ways would almost certainly illustrate areas where we could improve how we connect with students, faculty, and senior leadership.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I have to go make some content. (yarrr!)

2018 Peppoli Chianti Classico

I suspect Ben Franklin would be more of a côtes du rhône man, but on Friday evenings I like to imagine him kicking back with a vibrant chianti at an Italian cafe in Paris. This 2018 bottle is mostly Sangiovese with other Tuscan reds blended in. On the nose, you get a face full of fruit (raspberry) with the suggestions of something so earthy it’s metal. A robust mouthfeel with fine white pepper prominently featured from start to finish. Tight tannin structure, with lingering hints of jalapeño and sour cherries.

On “looping in”

Tell me if you’ve heard this one before:

Person A emails Person B: Hi, Person B. I have a question about this thing.

Person B: I don’t have the answer to this, but Person C (cc’ed) does.

If you work in an office, you almost certainly have received an email like this one. Someone copies you on a message with the expectation that you will pick up the conversation and answer the question that Person A originally sent.

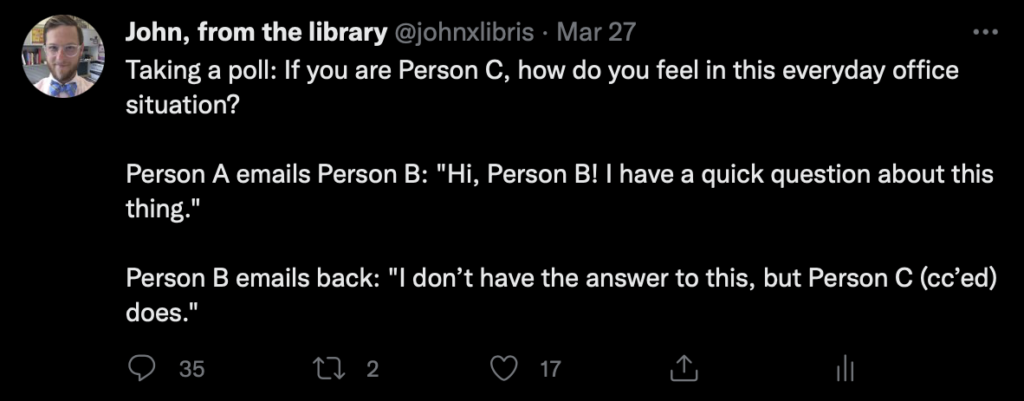

I posed question on Twitter and was surprised by the results.

Many of the responses didn’t think much of it: “happens all the time,” “this is normal,” “yeah, so?” etc. But far more were of the “it depends” variety: it depends on whether Person C actually knows the answer; it depends on whether Person B just wants to pass the buck on saying no; it depends on the power relationship between B and C.

Only one person mentioned what I find annoying about this [admittedly common] practice: that I don’t expect needing to respond to anything where I am in the cc line. Perhaps that is an indication of how long I’ve been on the internets: being in the cc means I need to be aware of this, but there is no expectation of needing a reply.

Email is messy.

Instead, what if Person B had reached out privately to Person C and said “Hey, Person A has a question. Can you (1) let me know how to respond or (2) if you would rather me to pass it on to you?” If Person C responds with #1, then Person B can send Person A an answer to their question directly. If they respond with #2, then Person B can connect to Person A to Person C.

This action offers the additional benefit of confirming that Person C is indeed the right person to handle the inquiry. If not, Person B can search elsewhere in the organization for the right person to contact and avoid sending Person A on a wild goose chase.

While this results in a small amount of extra work, it has a few benefits: (1) Person A will get the response they need in fewer steps. (2) Person B takes an active role in the inquiry. (3) Person C has the option to delegate the inquiry to Person B, rather than being obliged to take it on themselves.

Admittedly, this whole situation falls squarely into the category of “pet peeves.” I don’t make a fuss about this if someone on my team does this (and it happens all that time). However, in situations where I am Person B, I’ve been trying to seek out answers for Person A rather than quickly pass the buck to a colleague, even when that would be more convenient for me. In most cases, Person A reached out to me because I was a trusted contact, and so I appreciate the opportunity to reinforce that trusting relationship by not wasting their time and shuttling them around via email.

That said, I do wish we would stop cc’ing people if they are actually expected to respond. 😉