At some point, the cost of dealing with trolls and misinformation on social media, combined with diminishing returns on engagement, will outweigh the benefits of spending library time and resources in those spaces. What then? In some ways, it feels like we’re already there.

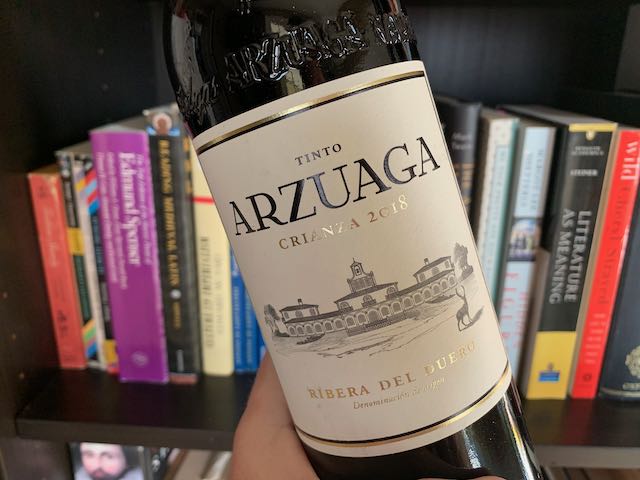

2018 Tinto Arzuaga Crianza

Wines from this DOP in Spain (Ribera del duero) must be aged at least two years, 12 months of which must be in oak. The influence of the oak definitely comes through here. Hot on the nose with lots of spice and vanilla. This vintage is juicy, with intense blueberry and cigar. The tannin structure is good: I should buy a few more bottles to store for 2-3 years.

How I work: a readme file

Recently, a colleague asked me about my daily time management practices. Having had this same conversation a few times already with others, I finally set myself to drafting a “readme” file for my communication and calendaring habits. This doesn’t include all the minutiae of my weekly productivity workflows, but it’s a top-level summary that (I hope) gives just enough detail to help my team understand why (1) my calendar is so booked and (2) why I don’t always respond to email or DMs right away.

My practices are built on the ideas of Cal Newport, Celeste Headlee, and David Allen, all of whom recommend intentional, process- and outcomes-focused modes of work.

Caveat: The following habits won’t work for everyone. It works for me, in my current position, with my current team and projects, etc. I offer it as an example of what one possible readme statement looks like.

How I communicate

Rationale: As much as possible, I try to reduce the need for unstructured, asynchronous communication in my work (what Newport calls the hyperactive hive-mind) and limit the amount of time I spend context-switching between tasks. Studies consistently show that long periods of focused, uninterrupted work produce higher-quality output and reduce the danger of creative fatigue and burnout.

Practice: I set aside 30 minutes each day to process my email inbox. Additionally, I set aside 1 hour each day for drop-in conversations (in-person or online): this time functions like office hours and are first-come first served. I do not keep my email or chat clients open when I am working on a project and my device notifications (except from the Library Administration team, my partner, and my parents) are muted, so don’t use email if you need an immediate response.

What you can do: If your request is not time-sensitive, email me and I will respond to it usually within 2-3 business days. If you would prefer, but don’t necessarily need, a quicker response, send me a message on Teams and I will likely respond within 1-2 business days. If you need a response day-of, stop by or DM me during my office hours (usually MWF 2-3p and TR 1-2p). My Outlook calendar is up-to-date and openly readable.

But what if you’re not available? Then you wait. Unless of course you have a way to create more time in the day. =)

How I schedule my week

Rationale: After working as an academic librarian professionally for almost a decade, I have developed a fairly accurate sense of exactly how much time I need to do various tasks that my job requires of me. For example, I know I can stay on top of my collection development work by dedicating 1.5 hours a week to the task. With this knowledge, I schedule my work week in advance using a “time-blocking” method, thus making sure I have adequate time to accomplish as much as possible within the time allotted to me (i.e., time that isn’t set aside for a meeting) each week.

Practice: At the end of each week, I review my tasks, projects, and annual goals and use them to map out the following week. Every hour of the day is given an assignment, with preference for longer periods of concentrated work (e.g., usually 1.5 hr blocks). In order to make time for focused work, I limit the amount of time I spend in-meetings each day to 3 hours. The first 30 min of each day is dedicated to checking in with my team and reviewing our essential tasks for that day. Additionally, because I often work 9-10 hour days, I schedule longer lunch breaks (1.5 hours max). I do not schedule meetings during that time and use that time to step away and recharge.

What you can do: As noted above, I try to leave 1 hour every day unscheduled as an office hour. Feel free to drop in in-person or virtually during that time. If you want to request a time on my calendar, you can schedule a time with me using Microsoft Bookings (external colleagues) or Outlook (internal colleagues).

But what if you don’t have any free time? It is true that I keep a lot of plates in the air at all times. This often means my calendar is booked for weeks at a time. However, if you send me an email requesting a time to meet (please send me 2-3 available times), I will try to move things around.

The criticism I usually receive about this style of working is that it is “closed door” (as opposed to “open door,” whatever that means*). Yes, it is true that I do more than most people to make myself unavailable to others. My current job requires sustained periods of concentrated work: to write long-form narratives, design graphics, plan out project timelines, run data analyses in spreadsheets, and proof materials. So much proofing. If I am frequently interrupted during these activities, I risk making critical mistakes that are costly to reverse.

All of us have alternating periods of “available” and “not-available” throughout the day. When I am in a meeting with my dean, it’s simple: I’m not available to answer a phone call. If I’m attending a speaker event on campus, I’m not responding to email. If I’m recording a video tutorial, I need to make sure no one knocks on my door! The question we sometimes fail to ask is: are there other moments when I should consider myself to be unavailable? Ones which, though the surrounding external friction/barriers are weaker, still merit an intentional “attention block” from outside influences? How would the quality of my work and, more importantly, the quality of my experience improve with less context-switching and fewer interruptions?

Just because you don’t have a meeting on your Outlook calendar does not mean you are “available.”

Nonetheless, I make a point to always set aside some time each day for drop-in conversations. During those office hour blocks, I don’t schedule any essential work: my only goal is to be open and available to others. If no one needs to chat, I will often use that time to follow up on requests sent via email. My office hours could alternatively be called my “synchronous communication hours.”

Is this convenient to everyone? No, but it provides an intentional space for things that need day-of input (and, in my experience, most things in academia don’t need day-of input… it’s just nice). I can’t offer you all of my time, but what I can offer, I can offer consistently.

*A note about “open door” practices: For me, having an open door management style is not synonymous with literally having your office door open or (in the case of not having a physical door) being always amenable to interruptions. Instead, my open door management style focuses more on whether I am providing consistent and frequent opportunities for team input, whether I am actively listening to that input, and whether I am able to take what I learn from that input and translate it into meaningful ways to support my team. And sometimes, the best way I can support my team is by closing my door and getting shit done.

ROOTs for 2022

Like many bibliophiles, I’ve accumulated more books than I actually have time to read. If you stacked all my books on top of each other, they would reach a height of 145 feet. That’s just shy of the Statue of Liberty (minus the pedestal). I acquired most of books in the decade between 2006 and 2017: the years when I was working on my M.A. and M.L.I.S degree and shortly after. Ironically, this was also when I was the most cash-strapped, and so I frequently sought out local used book sales in order to find copies on the cheap, which unexpectedly resulted in purchasing more books than was probably wise.

I’ve been trying to read more of what I already own instead of checking out or purchasing new titles. Within one LibraryThing community, this is called ROOTing: reading our own tomes. Last year, I was able to read about a dozen of my owned-but-not-read books, or ROOTs, and plan to continue the practice.

Reading one ROOT per month seems achievable. Here’s my list for 2022 (in no particular order):

- I, Robot / Isaac Asimov

- I Hope We Choose Love / Kai Cheng Thom

- Steppenwolf / Herman Hesse

- Unfinished Tales / J.R.R. Tolkien

- The Book of the Courtier / Castiglione

- Vineland / Thomas Pynchon

- Wide Sargasso Sea / Jean Rhys

- Five Dialogues / Plato

- Subtle Acts of Exclusion / Tiffany Jana and Michael Baron

- On Poetry and Poets / T.S. Eliot

- Opera and Its Symbols / Robert Donington

- A Short History of Philosophy / Robert C. Solomon and Kathleen M. Higgins

There wasn’t much of a science behind this list: mostly just titles I kept passing by while muttering to myself “yeah, I should read that.” Inevitably, I will pick up other books along the way (I’m already reading “Self-Compassion” by Kristen Neff while also reading “I Hope We Choose Love”), but having a realistic goal of one per month should allow me to balance somethings old with somethings new.

Don’t do it

I know you’re anxious about starting the new semester next week. I am, too. But it’s still Sunday. Enjoy what is left of your holiday. Don’t send that email.

Future thinking for 2022

I did not imagine that I would leave almost half a year between posts. From the evidence of this blog, one might think that I did not succeed at my 2021 goal to write more. However…

Not only did I journal more in 2021 than in previous years, I also wrote three scholarly articles for publication (two of which have already been accepted and/or published) and one case study for a colleague’s monograph. Remarkably, I also read more books last year (25) than I have read in a single year since I was a graduate student more than a decade ago.

So I’m happy with the results from my 2021 future thinking and want to build on that success in 2022. I still plan to set aside time for writing projects– including journaling, blogging, and scholarly articles– and, more generally, working to increase my career capital through intentionally focusing on rare and valuable skills, notably: project management, workplace kindness, and draft-making. As time permits, I also plan to dive deeper into various systems for project management and Excel as a tool for maximizing PM success (I see Gantt charts in my future).

Ultimately, I want to position myself so that I can easily take on high-impact projects: program assessment, strategic planning, and relationship building (ie. with stakeholders), but doing more will at first require doing less, as well as continuing to be intentional about how I use my time (see also: time-blocking). Shutting down all but one of my social media profiles (and minimizing my use of the remaining one) helps, too.

Related:

Eight hours for what you will

Academia’s work hours are weird. So is our approach to work[ing]. So much of our identity is wrapped up in that work. The same could be said of libraries in general; and so I imagine this is doubly problematic for academic librarians. A 2018 study by Tamara Townsend and Kimberly Bugg found that 40% of academic librarian respondents would consider leaving their current position to achieve greater work-life balance, and 31% of respondents would consider leaving the profession as a whole to achieve a greater work-life balance. That is a staggering statistic!

I believe that many of us in academic libraries (for a time, myself included) feel that our work is unique: that it requires us to give up more of ourselves for some “common good” (see also: vocational awe). But the same could be said of a host of other occupations: what makes our work any different?

This thinking is probably why I was so attracted to this opinion piece in the New York Times by Bryce Covert, who writes on the economy, with an emphasis on policies that affect workers and families. As she points out:

Studies show workers’ output falls sharply after about 48 hours a week, and those who put in more than 55 hours a week perform worse than those who put in a typical 9 to 5.

Among the participants in the studies Covert cites we find munitions workers, IT professionals, and civil servants. Add to this the negative long-term effects on one’s health, what benefit is there to academic librarians to regularly push work (especially scholarship) into our leisure time? Covert concludes:

We have to demand time off that lasts longer than Saturday and Sunday. We have to reclaim our leisure time to spend as we wish.

For the past few months, I have been consistently limiting my work hours to be as close to a “normal” 40-hour week as possible. This covers not only my performance duties (ie. librarian work), but my scholarship and service as well. Surprisingly to me (though, not surprising to anyone who has studied this phenomenon), I not only feel more accomplished, but I am able to mentally close up shop each day with less of a struggle.

I continuously encourage my team to do the same, and try to set an example for my colleagues by, for example, not responding to emails or sending DMs outside 9-6 hours, or always trying to estimate how much time I am asking of someone before I request support on a project. Even though burnout is as much (if not more) an organizational problem and not entirely the result of individuals’ actions, I still feel I should make personal changes where I am able.

When trees speak

In his collection of writings, Hermann Hesse said, “Whoever has learned how to listen to trees no longer wants to be a tree. He wants to be nothing except what he is” (h/t Brain Pickings). I reflected on this quote as a walked among the California redwoods last week during the first family vacation we had taken in over two years.

Hesse’s words were paired with the ideas I’m currently digesting in Jenny Odell’s How To Do Nothing. In particular, there is moment when Odell discuses the connection between proponents of a “personal brand” and seeking authenticity within the context of capitalism. After illustrating this nexus using Spotify’s Discover Weekly playlist, she notes:

When the language of advertising and personal branding enjoins you to “be yourself,” what it really means is “be more yourself,” where “yourself” is a consistent and recognizable pattern of habits, desires, and drives that can be more easily advertised to and appropriated, like units of capital. In fact, I don’t know what a personal brand is other than a reliable, unchanging pattern of snap judgments: “I like this” and “I don’t like this,” with little room for ambiguity or contradiction.

Hiking in northern California didn’t offer me much time for quiet reflection–what with also trying to make sure Mr. 5 didn’t fall down a mine shaft–but it did give me time to be with a version of my self that wasn’t trying to be a specific version of my self. I need these moments more and more these days, as I continue to [re]balance self care and vocational ambition.

Garden seeds and room

“Human life is a very simple matter. Breath, bread, health, a hearthstone, a fountain, fruits, a few garden seeds and room to plant them in, a wife and children, a friend or two of either sex, conversation, neighbours, and a task life-long given from within — these are contentment and a great estate. On these gifts follow all others, all graces dance attendance, all beauties, beatitudes, mortals can desire and know.”

via “The Secret of Happiness: Bronson Alcott on Gardening and Genius“

Not all of these elements of “a great estate” may be for everyone, but for me, this reflection rings especially true. Moreover, the more time and attention I give to these things, the less need I seem to have for doom scrolling and social media.

Randomly accessed memories 2021-04-26

When I need a mind-numbing activity to waste a few minutes of my day, rather than doom scrolling Twitter or needlessly refreshing my inbox, I like to hit the “random” button on some of my personal repositories of knowledge. I enjoy the exercise of thinking about where I was when I saved that webpage or liked that song or posted that quote. Here’s a quick sample from a recent trip down randomly accessed memory lane.

Random book from my library

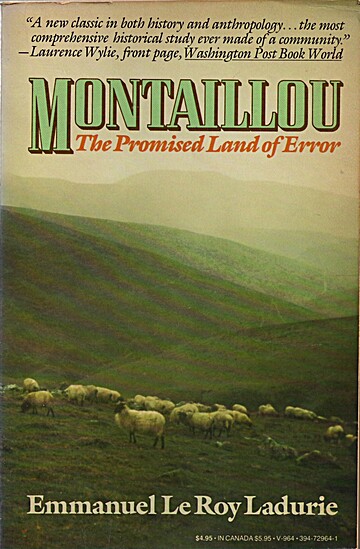

Montaillou : the promised land of error by Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie.

This is definitely a book I plan to read again. I first encountered it in 2006 while studying medieval literature in grad school. It’s a lovely (albeit disturbing) retelling of heresy in a small, French town based on an abundance of textual, “first-hand” knowledge that shows us more about life in rural Europe than it does about religious deviance.

Random bookmark

I saved this YouTube video back in September 2017. Apparently, by that point I was already on the Cal Newport train.

Random blog post

In 2016, I wrote about #LISMentalHealth, my chronic illness, and my decision to seek professional support to help manage my stress, anxiety, and depression.

Random word from the OED

nash, intransitive. To leave in a hurry, quit; to ‘dash’.

Random song

I don’t remember adding this to my library, but any time a song from this album comes on it makes me smile. Steven was right.